Do you want to subscribe?

Subscribe today.

Cancel SubscribeWhen you open this pub again using this browser, you'll be returned to this page. When you move to the next page the bookmark will be moved to that page (if you move back the bookmark will remain on the furthest page to which you've read). By touching the bookmark you can set the bookmark to whichever page you are on.

More bookmark features coming soon.

You must login to publish and add your own notes. Eventually you will be able to see others contributions if they make them public.

More notes features coming soon.

by Richard Maurice Bucke

Part 2

William Douglas O'Connor.

TWO SUBSEQUEXT LETTERS.

A NOTEWORTHY incident following the publication of Mr. O'Connor's pamphlet is embodied in the subjoined correspondence. The defence of the poet appears to have been received by the literary journals of the United States with a complete unanimity of abuse and ridicule. Among these reviews was one in the New York " Round Table" of January 20th, 1S66, penned by a minor poet, of considerable distinction in New York literary circles, Mr. Richard Henry Stoddard. His article, written in a vein of flippant insolence and containing a number of insulting references to Mr. O'Connor's previous literary work, was nevertheless relieved by the admission, however carelessly made, that Mr. Harlan '• deserved and deserves to be pilloried in the contempt of thinking men for this wanton insult to literature in the person of Mr. Whitman." This remark, imbedded in a column of rude persiflage, like a filament of gold in an acre of sage and alkeli, was the only observation adverse to Mr. Harlan's act which appeared in any American literary journal, and appears to have suggested the necessity for tlie following curiously clumsy and lying parry, made a week later (January 27th) in the " Round Table" by Mr. Charles Lanman, a gentleman of considerable literary pretensions, the author of the " Biographical Dictionary of Congress," formerly, it is said, secretary to Daniel Webster, and at this time one of the officers of the Interior Department under Mr. Harlan. The line of defence chosen for the Secretary by one of his officers and friends is so extraordinary as to add a

new feature of outrafre to an already sufficiently scandalous transaction. Mr. Lanman's communication was as follows :

Washington, January 19th, 1866. To THE Editor of the " Round Table."

Sir: Your notice of "The Good Gray Poet" contains one important error that I desire, as a friend of Secretary Harlan, to correct. You intimate, or, rather, reiterate the charge of Mr. Walt Whitman's defender—that the author of Leaves of Grass was removed from a clerkship because of his religious opinions. To this statement I give the most positive denial; and to substantiate it I have only to mention the fact that there are employed in the Interior Dci)artment gentlemen of every possible shade of religious opinion. Although the lion. Secretary is a high-minded and Christian gentleman, he has never, in a single instance, questioned an employe in regard to his religious belief, and for the very good reason that with those beliefs he has nothing to do. Nor is he in the habit of removing subordinates from office for their political opinions. Drunkards and incompetent men he does not consider fit to be intrusted with the business of the nation, and when such men are reported to him, they are very likely to be discharged. For removing Mr. Whitman from a clerkship there were two satisfactory reasons: he was wholly unfit to perform the duties which were assigned to his desk; and a volume which he published and caused to be circulated through the public offices was so coarse, indecent, and corrupting in its thought and language, as to jeopardize the reputation of the Department.

Respectfully yours,

Charles Lanman.

To this indescribable document Mr. O'Connor replied in the " Round Table " of a week later (P'ebruary 3d) as follows:

Washington, January 26th, 1866. To THE Editor of the "Round Table."

Sir : Allow me a few words of reply to Mr. Charles Lanman's extraordinary letter in your last issue respecting the accusation brought against Mr. Harlan by my pamphlet, " The Good Gray Poet."

As the statements of that letter are unfounded in every particular, they are probably as unauthorized as they are gratuitous. Nobody ever charged that Mr. Whitman was removed by the Secretary of the Interior "because of his religious opinions." I certainly made no such charge, nor did your reviewer.

Mr. Lanman's other assertions are equally hardy. It is not true that Mr. Whitman was removed because " he was wholly unfit to perform the duties which were assigned to his desk." On the contrary, Mr. Ilarian himself said at tiie time of the dismissal that he had no fault to find with Mr. Whitman in

regard to the performance of his official duties, but that he was discharjjed solely and only for being the author of Leaves of Grass. Nor is it true that Mr. Whitman was removed because he published and circulated in the Department any volume whatever. Leaves of Grass w as published years ago, and has been for some time out of print. " Drum-Taps," Mr. Whitman's recent book, consists mainly of poems of the war, and does not contain one word that even Mr. Harlan could accuse.

This disposes of Mr. Lannian's statements. But I note the color he gives his letter by the insinuated word " drunkards," and whenever he has the courage to put that as a charge which he has only ventured to put as an innuendo, I may deal with it and him.

The facts are precisely as I have stated them in my pamphlet, and whatever rejoinder any volunteer may choose to hazard, those facts ^Ir. Harlan himself ivill ne-t'er deny.

You will, perhaps, permit me this opportunity to express my obligations to your reviewer. In his notice of my pamphlet he says that the Secretary of the Interior " deserved and deserves to be pilloried in the contempt of thinking men for this wanton insult to literature in the person of Mr. Whitman." I thank him for those words. Coupled with such a condemnation of the outrage I denounce, no affront, no ridicule heaped on me or my writings can excite in my mind any feeling unmixed with gratitude. Shaftesbury, in England, is, if report says truly, a bigot peer, and Walter Savage Landor wrote poems which almost rivalled the license of the Roman; but if ever tiie lord, as the head of a Department, had dismissed the poet from an official station for his verses, the British press, whatever it thought of the poetry, would have stirred from John o' Groat's to Land's End with a tumult of denunciation whose impulse would have swept over the continent. I want a similar spirit here; and it matters very little what is said of my compositions, if the press and people of this country, by their resentment at an attempt to impose checks and penalties on intellectual liberty and the freedom of letters, and by their rebuke of a gross violation of the proprieties of the administration of a great Department, show that they are not below the decent level of Europe.

Very resjiectfully,

W. D. O'Connor.

PART II.

HISTORY OF LEAVES OF GRASS. ANALYSIS OF THE POEMS. ANALYSIS CONTINUED. APPENDIX TO PART H.

(133)

When the true poet comes, liow shall wc know him—

By what clear token,—maimers, lani^uage, dress? Or shall a voice from Heaven speak ami show him:

Iliin the swift healer of the l'"-arth's distress 1 Tell us that wlien the loiii:; expecteil comes

At last, with miith and mehidy ami singing, We him may greet with banners, beat of drums,

Welcome of men and maids, and joy-bells ringing; And, for this poet of ours, Laurels and (lowers.

Thus shall ye know him—tliis shall be his token:

Manners like other men, an unstrangc gear; His speech not musical, but harsh and broken

Shall sound at first, each line a driven spear; For he shall sing as in the centuries olden,

Before mankind its earliest fire forgot; Yet whoso listens long hears music golden.

How shall ye know him? Ye shall know him not Till ended hate and scorn, To the grave he's borne.

Richard Watson Gilder.

(»34)

CIIAPTKR I.

J/ISTOR V 01' LliA VJ'iS 01' CRASS.

Wai/p Whitman began to write for the i^eriodiral press at the age of fourteen years—was engaged as editor at maturity and afterwards—and continues as conlrii^utor to newspajjers and magazines to tliis day. If all he has ever written were eolleeted, it would probajjly make many good-sized volumes. 1 have no knowledge of any of the pieces in Leaves of Grass before the publication of the first edition in 1855. Walt Whitman tells us in one of the prose prefaces preserved in Specimen Days, that he had more or less consciously the plan of the poems in his mind for eight years before, and that during those eight years they took many shapes; that in the course of those years he wrote and destroyed a great deal; that, at the last, the work assumed a form very different from any at first expected ; but that from first to last (from the first definite conception of the work in say iH53-'54, until itscompletion in 1881 j his underlying purpose was religious. It seems that so much was clear in hi:; mind from the beginning, but how the plan was to be formulated seemed not at all clear, and had to be toilsomely worked out. A great deal else, of course, had to be present in his mind besides the intention. In the "Song of the Answerer," enumerating other elements necessary for such an enterprise, he says,

Divine instinct, breadth of vision, the law of reason, health, rudeness of body,

withdrawnness, Gayety, sun-tan, air-sweetness—such are some of the words of poems,

I'hesc he had, and beneath all, and above all, and including all, lying below consciousness, he had in unijaralleled perfection that rarest master faculty which we call moral elevation. Along with these, his race-stock, immerliate ancestry, mode of upbringing, outer life, surroundings, and American equipment, have to

('35)

be taken into account. It is upon these that he himself always lays the most weight. He once said to the present writer, *' The " fifteen years from 1840 to 1855 were the gestation or formative " periods of Z^-.rrri- of Grass, not only in Brooklyn and New York, "■ but from several extensive jaunts through the States—including "the Western and Southern regions and cities, Baltimore, Cin-'' cinnati, Chicago, St. Louis, New Orleans, Texas, the Mississippi "and Missouri Rivers, the great lakes and Niagara, and through " New York from Buffalo to Albany. Large parts of the poems, "and several of them wholly, were incarnated on those jaunts or "amid these scenes. Out of such experiences came the physi-" ology of Leaves of Grass, in my opinion the main part. The "psychology of the book is a deeper problem; it is doubtful "whether the latter element can be traced. It is, perhaps, only "to be studied out in the poems themselves, and is a hard study "there."

At another time, speaking with more than usual deliberation to a group of medical men, friends of his, in answer to their inquiries, on an occasion where I was present, he said, " One main " object I had from the first was to sing, and sing to the full, the " ecstasy of simple physiological Being. This, when full develop-" ment and balance combine in it, seemed, and yet seems, far "beyond all outside pleasures; and when the moral element and "an affinity with Nature in her myriad exhibitions of day and "night are found with it, makes f/ie /ia/>/>j' /\'rs(>//a//(\', the true "and intended result (if they ever have any) of my poems." This last sentence contains a key to the central secret o( Leaves of Grass —that this book, namely, represents a man whose ordinary every-day relationship with Nature is such that to him mere existence is happiness.

The problem then before him was to express not what he heard, or saw, or fancied, or had read, but one for deeper and more difficult to express, namely. Himself. To put the man Walt Whitman in his book, not especially dressed, polished, prepared, not for conventional society, but for Nature, for God, for America—given as a man gives himself to his wife, or as a woman gives herself to her husband—whole, complete, natural—with perfect love, joy,

anrl trust. This is something that, as I believe, was never before dared or done in literature. This is the task that he set for himself, and that he has accomplished. If the man were merely an ordinary person, such a purpose, such a book, written with absolute sincerity, would possess the most extraordinary interest; but Leaves of Grass has an interest far greater, derived from the exceptional personality which is embodied in it. Such was, in outline or brief suggestion, the intention with which it was written, and the reason for writing it. Then I think a profound part of the forecasting of the work was the way in which many things were left open for future adjustment.

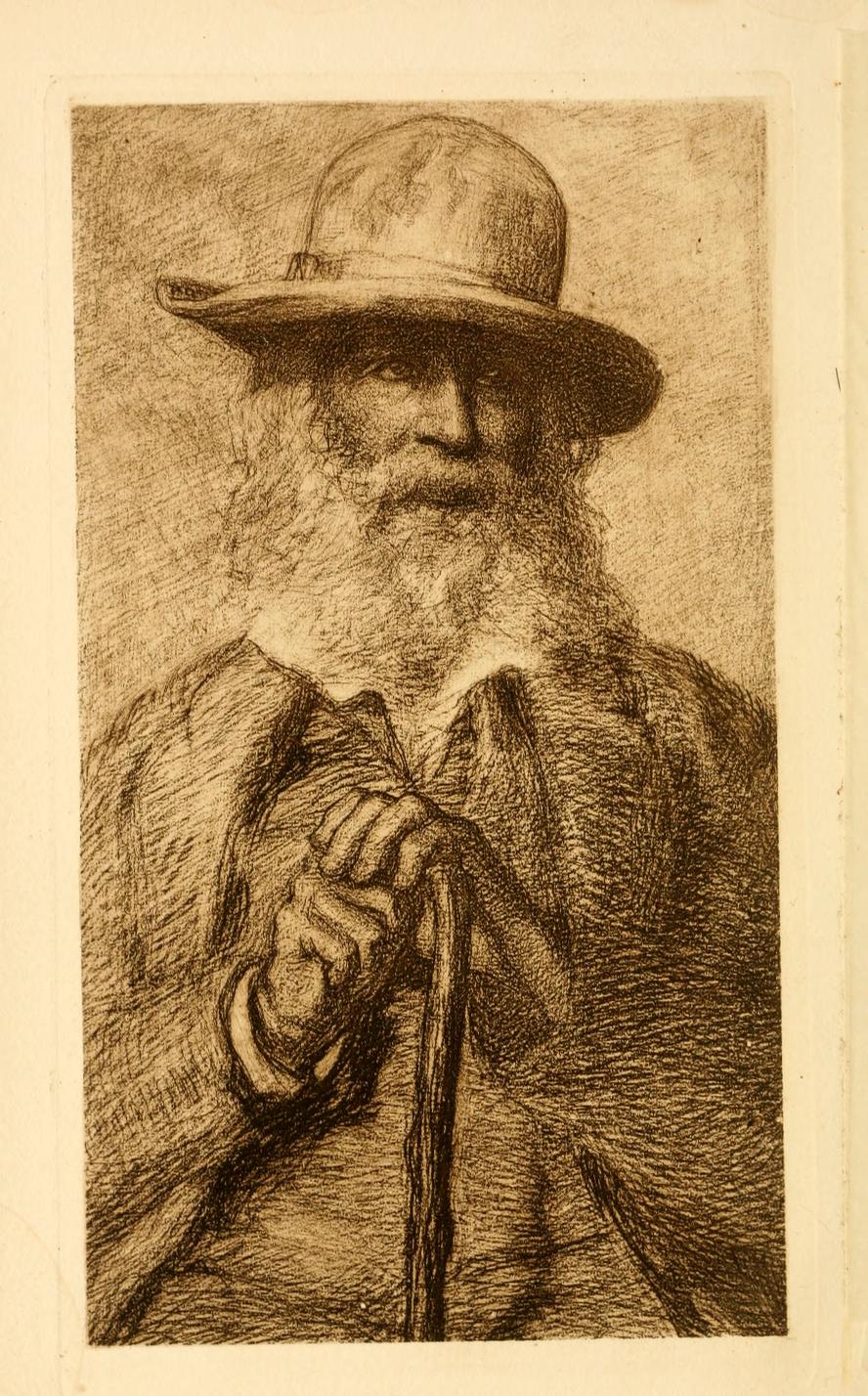

By the spring of 1855, Walt Whitman had found or made a style in which he could express himself, and in that style he had (after, as he has told me, elaborately building up the structure, and tlien utterly demolishing it, five different timesj written twelve I)oems, and a long prose preface which was simply another poem. Of these he printed a thousand copies. It was a thin quarto, the preface filling xii., and the body of the book 95 pages, on rather poor paper, and in the type printers call " English." The large title-page has the words " Leaves of Grass, Brooklyn, New York, 1855," only. Facing the title is the miniature of a man wlio looks about thirty-five to forty years old. He wears a broad-brimmed, wide-awake hat, has a large forehead and strongly-marked features. The face (to my mind) expresses sadness and goodnature. No part of the face is shaved. The beard is clipped rather short and is turning gray. The figure is shown down to the knees. This is Walt Whitman from life in his thirty-sixth year. The picture was engraved on steel by McRae, of New York, from a daguerreotype taken one hot day in July, 1854, by Gabriel Harrison, of Brooklyn. (The same picture is used in the current 1882 edition.) The twelve poems constituting the body of the book are unnamed, except for the words Leaves of Grass, which are used as a page heading throughout, and besides as a heading to some, but not all, of the individual pieces. Giving those twelve 1855 poems the names that they bear in the ultimate 1882 edition, the first eleven are:

1. Song of ^fysolf. 7. Sonc; of the Answerer.

2. A Sons; for (V\nip:\tions. 8. Kiiiope tlio 721! ami 7jil Years of ^ '1\> riiink of I'imo. These States.

4. The Sleepers. 9. A Roston Uallad (1S54).

5. 1 Sinij tlie IJoily I'.leotiie. lo. There was a ChiUl went forth.

6. laoi's. II. Who 1,earns my Lesson complete.

The twelfth, though ret.iineil in every cdilioii mUil the present, 1SS2, i.s omittetl from that. Its name in the 1876 eilition is "Great are the Mytlis."

The book now beinj:; nianufaetured, eojues of it were left for sale at various bookstores in New York ami Brooklyn. Other copies were sent to niaga/.iiies anil newspapers, and others to prominent literary men. Of those that were plaeed in the stores none were sokl. Those that were sent to the jiress were, in quite every instanee, either not notieed at all, laughed af, or reviewed with the bitterest and most scurrilous language in the vocabulary of the reviewer's contempt. Those sent to eminent writers were in several instances returneil, in some cases accomjianied by insulting notes.

The first reception of Le\jrcs of Grass by the world was in fact about as disheartening as it could be. Of the thousand copies of this 1855 edition, some were given away, most of them were lost, abandoned, or destroyed. It is certain that the book cpiite universally, wherever it was reail, excited ridicule, disgust, horror, and anger. It was considered meaningless, badly written, filthy, atheistical, ami utterly reprehensible. And yet there were a few, a very few iiuleed, who suspected from the first that under that rough exterior might be something of extraordinary beauty, vitality, and value. Among these was Ralph Waldo Emerson, then at the height of his splendiil lame. He wrote to Walt Whitman the following letter:

CoNCoun. Mass., Jitlv 21st, /Sjj. Dear Sir, —I am not bl'nul to the worth of the womlerfiil j^ift of Leaves 0/ Grass. I liml it tlie most e\traorilinary piece of wit and wisdom (hat America has yet contrilnitiii. I am very happy in reading it, as great jiower makes us happy. It meets the demaml 1 am always making of what seems the sterile and stingy Mature, as if too much liandiwurk ur too much lymph

in the temperament were making our Western wits fat and mean. I give you joy of your free and hravc thought. I have great joy in it. I find incom-jKirablc things, said incomparatjiy well, as they must ije. I find the courage of treatment wliich so delights us, and which large percejjlion only can inspire.

I greet you at the beginning of a great career, which yet must have had a long foreground somewhere, for such a start. I rubbed my eyes a little, to see if this sunbeam were no illusion; hut the solid sense of the book is a sober certainty. It has the best merits, namely, of fortifying and encouraging.

I did not knrjw, until 1 la:,l night saw the book advertised in a newspaper, that I could trust the name as real and available for a post-office.

I wish to see my Intnefactor, and have felt much like striking my tasks, and visiting New York to pay you my respects.

K. W. Emkrso.v.

This letter was eventually published Tat first refused by Walt Whitman, but on second and pressing application he consented), at the request of Chas. A. Dana, then managing editor of the "New York Tribune." Though it could not arrest, it did service in partially offsetting the tide of arJverse feeling and opinion which overwhelmingly set in against the poet and his book. Walt Whitman has since been censured for printing a so-called private communication of opinion, not intended for the public. In answer to this, besides no proof that the letter was meant to be private, the editor of the '^Tribune," who was a personal friend of both Walt Whitnoan and Mr. Emerson, would probably have been a judge in such matters, and he sought it for the columns of his paper, as legitimate and proper to both parties. It may be mentioned here that vastly as the two men, R. W. Emerson and Walt Whitman, differ in the outward show of their expression, there are competent scholars who accept both equally, and use them to complement each other.*

The next year, 1856, the second edition of Leaves of Grass was published by Fowler & Wells, 308 Broadway, N. Y., but the

* Emerson i« the "knight-errant of the moral sentiment;" Whitman accepts the whole " relentless kosmOB," and theoretically, at least, sccrns to blur the dihtinction between right and wrong. Emerson's fjages are lilce beds of roses and violets; Whitman's like masses of sun-flowers and silken-tasselled maize. Emerson soars upward in I'lato's chariot over the " fliokering l>a;mon Mu\ " into the pure realm " where all form in one only form dissolves," and when he returns his iacc and his raiment are glistening with light caught from that pure

IVa// Whitman.

firm did not put its name on the title-page. The volume is a small i6mo. of 3S4 pages. The same miniature of the author is used. The words Lt\j7'i-s of Grass are the page-heading throughout that part of the volume containing the poems, and besides this general title, each poem has a name, but in no instance exactly the same as it bears in later issues. The total number of poems in this edition is thirty-two. The twenty new poems are—(giving them as before the names they bear in the 1882-83 edition) :

II. 12.

14.

Unfolded out of the Folds.

Salut au Monde.

Song of the Broadaxe.

By Blue Ontario's Shore.

This Compost.

To You.

Crossing Brooklyn Feny,

Song of the Open Road.

A Woman Waits for Me.

A poem a large part of which is left out of the later editions, but which is partly preserved in "On the Beach at Night Alone."

Excelsior.

Song of Prudence.

A poem which now makes part of the "Songof the Answerer."

Assurances.

15. To a Foil'd European Revolu-

tionaire.

16. A short poem part of which is

afterwards incorporated in " As I sat Alone by Blue Ontario's Shore," and the rest of it omitted from subscciueat editions.

17. Miracles.

18. Spontaneous Me.

19. A poem called "Poem of The

Propositions of Nakedness," afterward called " Respondez," and printed in every edition subsequent to the 2d down to that of i882-'3—but omitted from that.

20. A Song of the Rolling Earth.

The prose preface of the first edition did not appear as such in this second edition, but part of it was embodied in a few of the

world of perfect types. But Whitman is like the ash-tree Ygdrasil. whose triple fountain-nourished root symbolizes what was done, what is done, and what will be done, and the roaring storm-tossed boughs of it reach through the universe and bear all things in their arms. Emerson is the sweet and shining Balder ; Whitman, Thor with hammer and belt of strength. Toss into the sunlight a handful of purest mountain lake water ; the thousand droplets that descend, flash and burn with whitest light, and on the silvery surface of each a miniature world lies softly pictured in richest iridescence. Like these droplets are Kincrson's sentences. But the writings of Whitman are the golden mirror of the moon lifted up out of immensity by some giant hand, that it may throw the refulgence of the sun down among the dark forests of earth, over its fair cities, sweet, flowery fields, and dark blue seas, concealing nothing, lighting earth's passion and its pain, its nuuders, its hatred and its hideousuess, as well as its music, its poetry and its flowers.— Lecture of W. Sloanb Kennedy.

new pieces, especially in " By Blue Ontario's Shore," " Song of the Answerer," "To a Foil'd European Revolutionaire," and "Song of Prudence." The poems extend to page 342. The rest of the volume, called " Leaves Droppings," is made up, first, of Pvmerson's letter to Walt Whitman, preceding—second, a long letter to Emerson in reply—and third, of twenty-six pages of criticisms of the first edition, taken from various quarters, a Iftwi favorable, the rest intensely bitter. (Extracts from some of these criticisms are given in the Appendix to Part II. of this vol.) Not only was this edition also savagely criticised, but so extreme was the feeling excited by it, that some good people in New York seriously contemplated having the author indicted and tried for publishing an obscene book. From this step they were only deterred by the consideration that, whatever might be the estimation which his book deserved, the man Walt Whitman was so popular in New York and Brooklyn, that it would be impossible to get a jury to find him guilty.

If any of the poems of Leaves of Grass can be put before the rest, we may say that upon the publication of the second edition the fundamental and important parts of the author's work were done, the foundations squarely and solidly laid, and the lines of the edifice drawn with a sure hand. The work, although far from completed, was already of supreme beauty and of infinite value. What then did men say of it? They received it with such a unanimous howl of execration and refusal, that after the sale of a small number of copies. Fowler & Wells, the publishers, thinking it might seriously injure their business, then very flourishing, peremptorily threw it up, and the publication ii^ Leaves of Grass ceased. For the next four years the history of the work is a blank.

I am not sure but the attitude and course of Walt Whitman, these following years, form the most heroic part of all. He went on his way with the same enjoyment of life, the same ruddy countenance, the same free, elastic stride, through the tumult of sneers and hisses, as if he were surrounded by nothing but applause ; not in the slightest degree abashed or roused to resent-

nient by the taunts and opposition. The poems written directly after the coUapse of this second edition (compare, for instance, " Starting from raumanok," and " Whoever you are, hoUling me now in hand,") are, if j^ossihle, more sympathetic, exultant, arrogant, and make hirger chiims than any. So far, the book had reached no circuU\tion worth mentioning; jirobably not a hui>-dred copies had been sold of both first and second editions. It is likely that at the time when the publishers of the second edition withdrew it from the market not a thousand people had read it, and not one in fifty of these would have the least idea what it was about.

Toward the end of the year 1S56 Thorean called npon Walt Whitman (Emerson had twice already visited him), anil shortly afterwards T. wrote a letter to a friend, extremely curious as showing the impression made by the poet at that time upon so fine a genius and so sensible a man as the Walden hermit. The uncertain tone of the letter, and the contradictions in it, are remarkably suggestive:

Concord, December ytli, 1S56.

Mr. B . . . . That W.ilt Whitman of whom I wrote to you is the most interesting fact to me at present. I have just read his second edition (which he gave me) and it has done me more good tlian any reading for a long time. Perhaps I remember best the " Poem of Walt Wiiitman, an American " [now called *' Song of Myself"] and the " Sun-down Poem " [now called " Crossing Brooklyn Ferry"]. There are two or three pieces in the book which are disagreeable, to say tlic least; simply sensual. He does not celebrate love at all. It is as if the beasts spoke. I think that men have not been ashamed of themselves without reason. No doubt there have always been dens where such deeds were unblushingly recited, and it is no merit to compete w^ith their inhabitants. But even on this side he has spoken more truth than any American or modern that I know. I have found his poem exhilarating, encouraging. As for its sensuality—and it may turn out to be less sensual than it appears— I do not so much wish that those parts were not written, as that men and women were so pure that they could read them without harm, that is, without understanding them. One woman told me that no woman could read it—as if a man could read what a woman could not. Of course, Walt Whitman can communicate to us no new experience, and if we are shocked, whose experience is it we are reminded of?

On the whole, it sounds to me very brave and American, after whatever

deductions. I do not believe that all the sermons, so called, that have been preached in this land, put together, are equal to it for preaching. We ought to rejoice greatly in him. lie occasionally suggests something a little more than human. You can't confound him with the other inhabitants of Brooklyn or New York. How they must shudder when they read him! He is awfully good. To be sure, I sometime feel a little imposed on. I5y his heartiness and broad generalities he puts me into a liberal frame of mind, prepared to see wonders—and, as it were, sets me upon a hill, or in the midst of a plain,—stirs me up well, and then throws in—a thousand of brick ! Though rude and sometimes ineffectual, it is a great primitive poem, an alarum or trumpet-note ringing through the American camp. Wonderfully like the Orientals, too, considering that, when I asked him if he had read them, he answered, "No; tell me about them."

I did not get far in conversation with him, two more being present—and among the few things that I chanced to say, I rememl^er that one was, in answer to him as representing America, that I did not think much of America, or of politics, and so on—which may have been somewhat of a damper to him.

Since I have seen him, I find that I am not disturbed by any brag or egotism in his book. He may turn out the least of a braggart of all, having a better right to be confident.

He is a great fellow. H. D. T.

During i857-'8-'9 Leaves of Grass was out of print. In i860 a third edition appeared, very much larger and handsomer than either of the preceding, publi.shed by Thayer & Eldridge, of Boston, beautifully printed on heavy white paper, and strongly bound in cloth—a volume of 456 pages, containing the 32 poems of the second edition, and 122 new ones. Many of the pieces have individual names, but most of them are named by groups. The words Leaves of Grass constitute the headline on the left-hand page throughout the volume; the right-hand page bears the name of the poem or group of poems. The likeness of the author, which accompanies the two earlier editions (and which appears again in the sixth as well as the late complete one;, is replaced in the third by another, only used in this edition ; an engraving on steel, from an oil painting by Charles Hine, (a valued artist-friend of Walt Whitman)—one of the most striking and interesting likenesses of the poet that has ever been made. The chief thing to note about this third edition is that not one word of the

poems which had given such terrible offence in the earlier issues is omitted. The author has not swerved a hair's breadth from the line upon which he set out. The volume breathes the same all-generous spirit as the earlier issues; the same faith in God, the same love of man, perfect patience, and the largest and most absolute tolerance. In this edition those poems treating especially of sexual passions and acts are, for the first time, grouped together under one name, "Children of Adam " (written here "En-fans d'Adam "), Walt Whitman was advised, urged, even implored by his friends to omit or at least modify these pieces. An old and intimate personal friend, urging him one day to leave them out, said to him, " What in the world do you want to put in that stuff for, that nobody can read ?" He answered with a smile, " Well, John, if you need to ask that question, it is evident at any rate that the book was not written for you."

In the course of the summer of i860, while Walt Whitman was in Boston, putting that third edition through the press, Emerson came to see him, and presently said, " When people want to talk in Boston, they go to the Common ; let us go there." So they went to the Common, and Emerson talked for something like two hours on the subject of " Children of Adam." He set forth the impolicy, the utter inadvisability of those poems. Walt Whitman listened to all he had to say; he did not argue the point, but when Emerson made an end, he said quietly, "My mind is not changed; I feel, if possible more strongly than ever, that those pieces should be retained." "Very well," said Emerson, " then let us go to dinner." *

* In "The Critic" for December 3d, 1881, Walt Whitman gives the following account of the interview : " Up and down this breadth by Beacon Street, between these same old elms, I walked for two hours, of a bright, sharp February midday twenty-one years ago, with Emerson, then in his prime, keen, physically and morally magnetic, armed at every point, and when he chose, wielding the emotional just as well as the intellectual. During those two hours he was the talker, and I the listener. It was an argument—statement—reconnoitring, review, attack, and pressing home (like an army corps in order, artillery, cavalry, infantry), of all that could be said against that part (and a main part) in the construction of my poems, ' Children of Adam.' More precious than gold to me that dissertation (I only wish I had it now verbatim). It afforded me, ever after, this strange and paradoxical lesson ; each point of E.'s statement was unanswerable, no judge's charge ever more complete or convincing—I could never hear the points better put—and then I felt down in my soul the clear and unmistakable conviction to disobey all, and pursue my own way. ' What

This third edition, which came out early in the summer of i860, was the first that had any sale at all. There was less outcry about it than about the first and second. A class of men had begun to appear—a very few—who, having more or less absorbed Leaves of Grass, were in a position to hold in check the army of detractors. Although it could not be said that public opinion was becoming even partially favorable, still a hearing was beginning to be established, and here and there both in America and England, individuals were rising up to defend the book and strike a blow in its advocacy. Just at this time when the enterprise looked encouraging, the Secession War ruined (among much else) the book-publishing trade. Thayer, Eld-ridge failed, and Leaves of Grass was again out of print. Soon after (in 1862) Walt Whitman went to the seat of war (see Specimen Days), and poetry was forgotten, or at least laid aside, in the vast, vehement, all-devouring interests and duties of the time, and the succeeding years.

Late in 1865 was published "Drum Taps"—poems composed on battle-fields, in hospitals, or on the march, among the sights and surroundings of the war, saturated with the spirit and mournful tragedies of that time, including in a supplement, "When Lilacs Last in the Door-yard Bloom'd," commemorating the death of President Lincoln. Then in 1867, the war being well over, and the ordinary avocations of peace resumed, the poet (he had at the time a clerkship in the office of the Attorney-General, at Washington) brought out the fourth edition, including all the poems written down to that period. This volume in size and shape is very similar to the current edition. It contains 470 pages and 235 poems. All the old ones are retained, and about 80 new ones added. The title-page bears the words "Leaves of Grass, New York, 1867." This fourth edition contains no portrait. It is fairly printed (from the type) on good paper, but is not nearly as handsome a volume as the third edition.

have you to say, then, to such things?' said E., pausing in conclusion. 'Only that while I can't answer them at all, 1 feel more settled than ever to adhere to my own theory, and exemplify it,* was my candid response. Whereupon we went and had a good dinner at the American House."

13

The fifth edition was issued in 1S71. It consisted of one good-sized, good-looking vohime (3S4 pages), and a brochure, same paper and type, called " Piissage to India" (120 pages). The total number of poems in this issue is 263—all the old, and a few new ones, especially the aforesaid "Passage to India." This edition was printed from new plates, on thick white paper, and is the handsomest edition published up to that time. In it all the old poems are carefully revised. This is known as the Washington edition. The title-page bears the words " Leaves OF Grass, Washington, D. C, 1871." This, like the fourth, contains no portrait. It supplied such moderate demand (mostly in England) as existed during five years.

Early in 1S72 Walt Whitman was invited by the students of Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, to deliver what is called "the Commencement Poem." He accepted, went on there, had a good time, and the piece given was published in book-form in New York soon after under the name of "As a Strong Bird on Pinions Free." It had no sale at all. (In the present, 1882 edition, it is called "Thou Mother with thy Equal Brood.")

In 1876 the author printed the sixth edition. This—for several reasons, the most interesting and valuable of all—is in two volumes, one called Leaves of Grass (printed from the same plates as the corresponding volume in the fifth edition), and the other, " Two Rivulets." The last named is made up of " Democratic Vistas," "Passage to India" (printed from the plates used in the fifth edition), and, along with these, four collections of prose and verse, called respectively, " Two Rivulets," " Centennial Songs, 1876," "As a Strong Bird on Pinions Free," and, in prose, " Memoranda During the War." The total number of pages is 734, and the total number of poems 288. Each volume contains the author's autograph, and the two books include three portraits. It will not be many years before copies of this Centennial edition will bring almost anything that holders of them like to ask. The poems contained in it are all included (with many alterations, some omissions, additions, etc.) in the 1882 issue; and most of the prose is included in Specimen Days,

The next Cseventh) edition of Leaves of Grass is that of James R. Osgood & Co., Boston, 1881-82. The text is packed as closely together as possible in one volume of 382 pages, long primer type, containing 293 distinct poems. A itvt of the old ones are omitted (generally for the reason that what they contained was expressed elsewhere), in some instances two are run into one, and quite a number of new pieces added. The text throughout has been thoroughly revised, hundreds of slight alterations have been made, in many places words and lines omitted, and as frequently, in other places, words and lines added. The arrangement and the punctuation have been materially altered for the better, and the poems are so joined and blended by slight alterations in the text and by juxtaposition, that Leaves of Grass now becomes a unit in a sense it had never been before. The original design of the author, formed twenty-six years before, has taken shape, and stands in this volume completed.

It is usual to speak, as I have done, of the different " editions" of Leaves of Grass, but this term, in one sense, is scarcely correct, for an essential point about the work is not only its identical but its cumulative character. Those seven different issues are simply successive expansions or growths, strictly carrying out the one idea.

A peculiarity of Walt Whitman has been his careful attention to the minutest details of typography (he is a printer himself, be it remembered) in all the issues of Leaves of Grass, and especially in the final one. Instead of sending on his copy and receiving back proofs by mail, he goes personally to Boston, takes a little room in the printing office, settles on the size of page, kind of type, how the pieces shall run on, etc. After which, for six or seven weeks, every line is vigilantly scanned ; every day for two or three hours he is at Rand & Avery's (the printing office and foundry) reading proofs, sometimes to the third and fourth revision. On the completion of the plates, he remarked that if there was anything amiss in the material body of the work, it should be charged to him equally with its spiritual sins, for he had had his own way about it all.

The subsequent withdrawal of the firm of J. R. Osgood & Co. from publishing that seventh edition of Leaves of Grass makes it necessary to relate somewhat in detail both how they came to be, and how, in a short five or six months, they ceased to be, such publishers. In May, 1881, J. R. Osgood wrote to Walt Whitman, asking if he had in hand and was disposed to bring out a new and complete edition of his poetic works. Walt Whitman wrote back that such an enterprise was contemplated by him, but before entering upon any negotiation, it needed to be distinctly understood that not a piece or line of the old text was intended by him to be left out; this was an absolute pre-requisite. Osgood & Co. then wrote asking if they could see the copy. Walt Whitman sent it immediately. Osgood & Co. wrote back formally offering to publish, and mentioning terms, which were fixed at a royalty of twenty-five cents on every two-dollar copy sold. The contract being made, the poet went on to Boston, and was there two months (September and October, 1881) engaged in seeing the poems properly set up. This seventh and completed Leaves of Grass was published latter part of November, 1881. The sale commenced fairly. Several hundred copies went to London, and Walt Whitman's royalty from the winter and early spring issues amounted to nearly five hundred dollars.

March ist, 1882, Oliver Stevens, Boston District Attorney (under instructions from Mr. Marston, State Attorney-General, see further on), sends an official letter* to Osgood & Co. that he intends to institute suit against Leaves of Grass and for its suppression, under the statutes regarding obscene literature. A list of pieces and passages is soon after officially specified, and it is

* Here is this curious document:

Commo.iwealth of Massachusetts,

District Attorney's Office, Boston, 24 Court House, Alarch ist, 1882. Messrs. J. R. Osgood & Co.

Gentlemen, —Our attention has been officially directed to a certain book, entitled Leaves of Crass, Walt Whitman, published by you. We are of the opinion that this book is such a book as brings it within the provisions of the public statutes respecting obscene literature, and suggest the propriety of withdrawing the same from circulation, and suppressing the edition thereof; otherwise the complaints which are proposed to be made will have to be entertained. 1 am, yours truly,

(Signed) Oliver Stevens, District Attorney,

intimated that upon these being erased and left out, the publication may continue. March 21st, Osgood & Co. write Walt Whitman, forwarding this list,* and asking if the words, lines, and pieces specified could be left out. March 23d, Walt Whitman writes Osgood & Co., " The list, whole and several, is rejected "by me, and will not be thought of under any circumstances." A week afterwards, Osgood & Co. write Walt Whitman, "The official mind has declared it will be satisfied if the pieces ' To a Common Prostitute ' and ' A Woman Waits for Me' are left out," and that those two so left out, the book can then go on unmolested. (Osgood & Co. add that they have suspended the publication and sales, and that orders are waiting.) Walt Whitman peremptorily rejects the proposal to leave out the two pieces. Osgood & Co. (April 13th, 1882) courteously but decidedly write that they cannot afford to be drawn into any suit of the kind threatened by the Boston officials, but must give up Leaves of Grass, and that they are ready to turn over the plates to Walt Whitman's purchase, (these plates were so consigned to him, and no cash royalty ever paid), adding, " We feel it right to say, that it is not we who have fixed inflexible conditions under which this matter could be decided—those conditions have been fixed by yourself." (There is an interior history of the persons and their animus behind the scenes, in Boston, who egged on Messrs. Mars-ton and Stevens, which has not yet come to the light, but may, some day.)

* The following is the list referred to—(same paging as in the 1882 edition):

PAGE LINES PAGE LINES

31, 15th and i6th. 88, 89, " A Woman Waits for Me."

32, igth to 22d (inclusive). 90, 91, Whole of 90 and 91, to line 11 (inclu-37, 14th and 15th. sive).

48, 20th to 29th (inclusive). 94, First si.\ lines and half of 7th to words

49, nth to 20th (inclusive). " indecent calls " (inclusive). 52, The remainder of paragraph twenty- 216, " The Dalliance of the Eagles."

eight, beginning at the i2th line. 266, 21st and 22d.

59, nth and 12th. 299, 300, " To a Common Prostitute."

66, 15th and i6th. 3°3. 2^ ^"d 3d.

79, 2ist and 22d. 32S) The remainder of the 4th line from

80, Entire passage from 14th line, ending bottom,heginning with words "he

with words "And you, stalwart with his palm."

loins," on page 81. 331. 9th and loth.

84, ist to 7th (inclusive). 355, 13th to 17th (inclusive).

87, 13th to 28th (inclusive).

After such plain narration of the facts, perhaps the keenest and most deserved comment upon this whole transaction (it was fitting that the one who attended to Hon. Mr. Harlan in 1865-6 should also sum up the Marston-Stevens-Osgood affair in 1882) is a letter by William D. O'Connor, printed in the "New York Tribune" of May 25th, 1882, from which the following are extracts :

If it were not for unduly trenching upon your space, I would like to show you the passages which the State District-Attorney pronounced obscene, and demanded expurgated. The list furnished by this holy and intelligent man is before me, and has twenty-two specifications. Four of the passages specified relate to the poet's democratic theory of the intrinsic sacredness and nobility of the entire human physiology—identical with the famous declaration of Novalis that the body is the temple of the Holy Ghost; and involve, specially in one or two instances, a rapt celebration of the acts and orga^ns of chaste love. Another passage describes the identification through sympathy of one's self with lawless or low-down persons. A sixth passage under ban is devoted to the majestic annunciation of woman as the matrix of the generations—the doctrine that her greatness is the mould and condition of all the greatness of man. Another proscribed passage consists of ten pictorial lines, worthy of yEschylus, in which the poet describes the grand and terrible dalliance of two eagles, high aloft in the bright air, above a river road. A seventh passage specially required to be expunged is the poem nobly entitled " To a Common Prostitute "—I say nobly, because even the large sense of the composition is enlarged by its title. The piece is simply indicative of the attitude of ideal humanity in this age toward even the lowest or most degraded, and is conceived throughout in the sublime spirit of our times, whose theory abandons no one nor anything to loss or ruin, recognizing amelioration as the law of laws, and good as the final destiny of all. It is incredible that a poem whose whole staple, on the face of it, is to assure the unfortunate Magdalen that not until Nature excludes her shall she be excluded from consideration and sympathy, and to promise her the redemption of the superior life—whose entire thesis is plainly and undeniably supreme charity and faith in the human ascension—should appear to any mind as an expression of obscenity. However, as Swedenborg reminds us, to the devils perfumes are stinks. The eighth quarry of the State District-Attorney is the piece entitled, " A Woman Waits for Me." If the defence of this poem is to carry with it dishonor, I court that dishonor. Nothing that the poet has ever written, either in signification or in splendid oratoric music, has more the character of a sanctus ; nothing in modern literature is loftier and holier. Beginning with an inspired declaration of the absolute conditioning power of sex—a declara-

tion as simply true as sublime—the poet, using sexual imagery, as Isaiah and Ezekiel, as all the prophets, all the great Oriental poets, have used it before him, continues his dithyramb in exalted affirmation of the vital procreative effects of his book upon the women, that is to say upon the future of America. And this glorious conviction of a lofty mission—the consciousness, in one form or another, of every philosopher, every apostle, every poet who has worked his thought for the human advancement—the faith and the consolation of every sower of the light who has looked beyond the hounding hatreds of the present to the next ages—the eminently pure, the eminently enlightened, the supereminently judicial Boston District-Attorney considers obscene! The remaining fourteen passages marked by his condemnation I need not discuss, as they are all included in the first edition of the work indorsed by Emerson.

As for the part taken by Messrs. Osgood & Company in this shameful transaction, what is said should have the conciseness of a brand. It was no new book they had undertaken to publish—it had been the talk of two worlds for over a quarter of a century. They knew its noble repute in the highest quarters, and they also knew what shadows might be cast upon it by booby bigotry, by foul sour prudery mincing as purity, or by rotten carnality in its hypocrite mask of virtue. Knowing all this, facing possible consequences in their agreement to publish without expurgation, and having voluntarily sought the publication of the volume, I say it was their duty as gentlemen to stand by the bargain they had solicited, and it was no less their interest as men of business to advertise the State-Attorney's ridiculous menace in the boldest type their printers could furnish, and bid him come on with his prosecution! Time enough to give in when Sidney Bartlett had failed to make a Massachusetts jury see that in literature we must allow free expressions if we are going to have free expression ;—time enough to own defeat when Sidney Bartlett or Charles O'Conor failed to make plain, as either would not have failed to make plain to even Mr. Oliver Stevens's comprehension, the difference between Biblical courage of language and intrinsic intellectual impurity. But Messrs. Osgood & Company leave their Pavia unfought, and lose everything, including honor. They might have braced themselves with the remembrance of Woodfall, standing prosecution heaped on prosecution, in his dark fidelity to Junius. They might have gathered grit by trying to imagine John Murray flinching from the publication of Byron. On the contrary, shaking in abject cowardice at the empty threat of this legal bully, they meanly break their contract with the author, abandon the book they had volunteered to issue, and drop from the ranks of great publishers into the category of hucksters whose business cannot afford a conscience.

It only remains to point the moral and adorn the tale with the name of the Boston District-Attorney. I have called the transaction in which he appears as the prime mover shameful, but the word is limp and colorless in its application to such an outrage upon the liberty of thought as he has committed.

The sense of it mal<es every fibre of one's being seem interknitted with lightning. On such a subject no thinking man or woman in such a country as ours will reflect with cold composure. The action of this lawyer constitutes a reef which threatens with shipwreck every great book of every great author, from Aristophanes to Moliere, from ^schylus to Victor Hugo; and the drop of blood that is calm in view of such an outrage proclaims us bastard to the lineage of the learned and the brave! To-day Oliver Stevens has become the peril of Shakespeare. He knows well, no one knows it better, that under his construction of the statutes neither Shakespeare nor the Bible could be circulated, and no one better knows than he that neither of those books is obscene. He knows well, Emerson and a host of scholars and men of letters in both continents bearing witness, that Walt Whitman's book is no more within the meaning of the statutes than Shakespeare or the Bible, but he also knows that the charge he has brought against the one lies with at least equal force against the others, and if he does not continue his raid upon the great literature, it is only because his courage is not equal to his logic. Even his bolder and brassier ally in this holy war, Mr. Anthony Comstock,—even he tempers valor with discretion for the nonce, and says he " will not prosecute the publishers of the classics, unless they specially advertise them" ! There are contingencies, it seems, in which the great works of the human mind will be brought under the operation of " the statutes against obscene literature." Who knows, since fortune favors the brave and enterprising, but that we may yet, step by step, succeed in bringing the Fourteenth century into tlie Nineteenth, and reerect Montfaucon—that hideous edifice of scaffolds reared by Philippe le Bel, where the blackened corpse of Glanus swung beside the carcass of the regicide for having translated Plato, and where Peter Albin dangled gibbeted beside the robber for having published Virgil? If this fond prospect is still somewhat distant, it is only, it seems, because Mr. Anthony Comstock lets his I dare not wait upon I would, and delays the initial step until the classics are "specially" advertised. Meanwhile Mr. Oliver Stevens also waits for fresh relays of courage, and as yet only ventures to attempt to crush Walt Whitman. For that act of daring he shall reap the full harvest of reward. We will see whether in this country and in this century he can suppress by law the work of a man of genius, and fail of his proper recompense. He has arrested in Massachusetts the superb book which is the chief literary glory of our country in the capitals of Europe—the book of the good gray nurse who nourished the wounded and tended many a dying soldier through our years of war—and for that valiant action I promise Mr, Stevens his meed of immortal remembrance. He has the solemn comfort of having been unknown yesterday; I can offer him the glorious assurance that he will not be forgotten to-morrow.

The Marston-Stevens-Osgood assault, however, instead of

bringing about the result intended (a suppression of Leaves of Grass), immediately produced quite the contrary effect. The book was taken up by a Philadelphia house, Rees Welsh & Co., to whose miscellaneous business David McKay succeeded, and the latter is now publisher both of the completed poems, and of the late prose work, Specimen Days. Of Leaves of Grass the firs<" Philadelphia edition (without the omission of a line or word) was ready in the latter part of September, 18S2, and all sold in one day. And there has been quite a general and steady sale since.

It is this issue, comprehending all, that I allude to throughout the present volume as the completed 1S82 (or i882-'83) edition. It includes several touches and additions, minor but significant, not in any previous issue.

CHAPTER IL

ANALYSIS OF THE POEMS, ETC.

Although, as already stated, Walt Whitman has written much else, yet the two now published volumes, 1882-83, the one of verse. Leaves of Grass, and the other of prose, Specimen Days a7id Collect, may be considered (at any rate so far) as containing all that he cares to preserve. For the purpose of comment, the prose writings may be divided into, First, the early tales and sketches in the Appendix, Secondly, the section of CV/Z?^/which includes several pieces of the highest excellence, entitling the author to take equal rank with the greatest masters of prose composition. These essays—especially "Democratic Vistas," "Origins of Attempted Secession," *' Preface to 1855 Issue oi Leaves of Grass,'^ ''Poetry To-day in America"—are not only of the greatest value inherently in themselves, but as presenting the prose, intellectual, discriminating, common-sense side of American Democracy, of which Leaves of Grass exhibits the poetical aspect. They thus counterpart one another, and the prose essays show (what if we read the poetry only we might be inclined to doubt) that the man who saw the future glories of American civilization which are set forth in the poetic work, saw also, and fully saw, the mean and threatening facts which are visible to ordinary men in the present, and which they (many of them) think is all there is to see. Thirdly, the first half, or third, of Specimen Days (formerly called " Memoranda during the War ") is, as far as I know, by far the best work yet written from which to get an idea of the Secession struggle of i860-'65—who were engaged in it, what they actually did, and how they felt and suffered. Its want of literary form makes it the more valuable. Had the author from his notes distilled a finished work, he must inevitably have included coloring and shading from his own after-feelings and ( 154 )

reflections; but as actually jotted down on the battle-fields and in the hospitals, surrounded by the events, scenes, persons depicted, it is clearly the reproduction of living incidents under the direct observation of the writer, absolutely truthful and unadorned. Fourthly, the last one hundred and twenty pages of Specimen Days stands in a category by itself; its correct name taken alone would be "The Diary of an Invalid," and it is as such that it has its extraordinary and unique value. As Leaves of Grass is, from one point of view, a picture of perfect ideal health, so may this section oi Specimen Days be received as the ideal (though entirely real) picture of sickness. It will remain forever a record of how a heroic soul faced and without dejection quietly and bravely passed through continued grief, poverty, the imminency of death, and great suffering both of mind and body, lasting for years. Never before from amid such circumstances came such a voice. Leaves of Grass teaches us to strive, to aspire, and to dare ; Specimen Days an equally good lesson, that of fortitude, cheerfulness, and even joyousness in defiance (though not in a spirit of defiance) of all and any ills.

Lastly comes Leaves of Grass, the real work of the author's life—or from another (and more correct) point of view the image of his real work, which was his life itself. After the long period of its own and its author's growth, we have it at last in the 1882 -'83 edition, completed as conceived twenty-six years ago. During that time every line has been pondered again and again with the greatest care. Though the result of spontaneity and spiritual impulse, and invariably started thence, the file has in no wise been forgotten. Every word and expression found not to come up to the standard has been cut out. The new material as prepared has been fitted into its place; the old, from time to time, torn down and re-arranged. Now it appears before us, perfected, like some grand cathedral that through many years or intervals has grown and grown until the original conception and full design of the architect stand forth.

In examining this book, the first thing that presents itself for remark is its name, by no means the least significant part. It

would indeed be impossible to select for the volume a more perfect title. Properly understood, the words express what the book contains and is. Like the grass, while old as creation, it is modern, fresh, universal, spontaneous, not following forms, taking its own form, perfectly free and unconstrained, common as the commonest things, yet its meaning inexhaustible by the greatest intellect, full of life itself, and capable of entering into and nourishing other lives, growing in the sunshine (/. e., in the full, broad light of science), perfectly open and simple, yet having meanings underneath ; always young, pure, delicate and beautiful to those who have hearts and eyes to feel and see, but coarse, insignificant and worthless to those who live more in the artificial, (parlors, pictures, traditions, books, dress, jewels, laces, music, decorations, money, gentility), than in the natural, (the naked and rude earth, the fresh air, the calm or stormy sea, men, women, children, birds, animals, woods, fields, and the like).

I might say here a preparatory word or two about the absence of ordinary rhyme or tune in Walt Whitman's work. The question cannot be treated without a long statement, and many premises. Readers used to the exquisite verbal melody of Tennyson and Longfellow may well wince at first entering on Leaves of Grass. So does the invalid or even well person used to artificial warmth and softness indoors, wince at the sea, and gale, and mountain steeps. But the rich, broad, rugged rhythm and inimitable interior music of Leaves of Grass need not be argued for or defended to any real tone-artist. It has already been told how, during the gestation of the poems, the author was saturated for years with the rendering by the best vocalists and performers of the best operas and oratorios. Here is further testimony on this point, from a lady, a musician and art-writer, Mrs. Fanny Raymond Ritter, wife of Music-Professor Ritter of Vassar College :

Those readers who possess a musical mind cannot fail to have been struck by a peculiar characteristic of some of Whitman's grandest poems. It is apparently, but only superficially, a contradiction. A fault that critics have most insisted upon in his poetry is its independence of, or contempt for, the canons of musico-poetical art, in its intermittent, irregular structure and flow. Yet the

characteristic alluded to which always impressed me as inherent in these— especially in some of the Pindaric " Drum-Taps "—was a sense of strong rhythmical, pulsing, musical power. I had always accounted to myself for this contradiction, because I, of course, supposed the poet's nature to be a large one, including many opposite qualities; and that as it is impossible to conceive the Universe devoid of those divinely musical forces, Time, Movement, Order, a great poet's mind could not be thought of as an imperfect, one-sided one, devoid of any comprehension of or feeling for musical art. I knew, too, that Whitman was a sincere lover of art, though not practically formative in any other art than poetry. Therefore, on a certain memorable Olympian day at the Ritter-house, when Whitman and Burroughs visited us together, I told Whitman of my belief in the presence of an overwhelming musical pulse, behind an apparent absence of musical form in his poems. He answered with as much sincerity as geniality, that it would i'ndeed be strange if there were no music at the heart of his poems, for more of these were actually inspired by music than he himself could remember. Moods awakened by music in the streets, the theatre, and in private, had originated poems apparently far removed in feeling from the scenes and feelings of the moment. But above all, he said, while he was yet brooding over poems still to come, he was touched and inspired by the glorious, golden, soul-smiting voice of the greatest of Italian contralto singers, Marietta Alboni. Her mellow, powerful, delicate tones, so heartfelt in their expression, so spontaneous in their utterance, had deeply penetrated his spirit, and never, as when subsequently.writing of the mocking-bird or any other bird-song, on a fragrant, moonlit summer night, had he been able to free himself from ihe recollection of the deep emotion that had inspired and affected him while he listened to the singing of Marietta Alboni.

The volume (final edition i882-'83) opens with ten pages of short poems called "Inscriptions," some of which were written after the body of the work, and are reflections upon its intention and meaning. They cannot be understood until the book itself has been studied, and its scope and power more or less realized. Here, for instance, is one of them :

Shut not your doors to me, proud libraries.

For that which was lacking on all your well-fiU'd shelves, yet needed most, I

bring. Forth from the war emerging, a book I have made, The words of my book nothing, the drift of it everj'thing, A book separate, not link'd with the rest, nor felt by the intellect, But you, ye untold latencies, will thrill to every page.

And here another:

Lo, the unbounded sea,

On its breast a ship starting, spreading all sails, carrying even her moonsails;

The pennant is flying aloft as she speeds, she speeds so stately—below emulous

waves press forward, They surround the ship with shining curving motions and foam.

The first of these, I suppose, could not be in any degree explained to a person who knew nothing of Leaves of Grass. The second admits of a certain degree of explanation v/hich, however, would have to be taken on trust by such a person. The ship is the book, the ocean is the human mind. The large ship, with all sails set, starts on her voyage ; as she presses through the water, the waves (the resistances the book meets) roll from her bows and down her sides. The angry, hostile criticisms and clamors are the bubbles of foam in the wake.

The first poem of any length, "Starting from Paumanok," appeared first in the third (i860) edition, though it was written in 1856, immediately after the second (1856) edition was published. It is an introduction or overture. In it the author sets forth what he is going to do. He says he intends to celebrate man's soul and his body—to drop in the soil of the general human character the germs of a greater religion than has hitherto appeared upon the earth. He says he will sing the song of companionship, and write the evangel-poem of comrades and of love. Referring to " Children of Adam," he says :

And sexual organs and acts! do you concentrate in me—for I am determin'd to tell you with courageous clear voice to prove you illustrious.

And toward the end of the poem, as a final admonition, he says to the reader:

For your life adhere to me;

(I may have to be persuaded many times before I consent to give myself

really to you—but what of that ? Must not Nature be persuaded many times?)

No dainty dolce afifettuoso I;

Bearded, sun-burnt, gray-neck'd, forbidding, I have arrived. To be wrestled with as I pass for the solid prizes of the universe, For such I afford whoever can persevere to win them.

The stress of the book opens with the poem (hitherto named "Walt Whitman," now) " Song of Myself," the largest and most important that the author has produced, and perhaps the most important poem that has so far been written at any time, in any language. Its magnitude, its depth and fulness of meaning, make it difficult, indeed impossible, to comment satisfactorily upon. In the first place, it is a celebration or glorification of Walt Whitman, of his body, and of his mind and soul, with all their functions and attributes—and then, by a subtle but inevitable implication, it becomes equally a song of exultation, as sung by any and every individual, man or woman, upon the beauty and perfection of his or her body and spirit, the material part being treated as equally divine with the immaterial part, and the immaterial part as equally real and godlike with the material. Beyond this it has a third sense, in which it is the chant of cos-mical man (the etre supreme of Comte)—of the whole race considered as one immense and immortal being. From a fourth point of view it is a most sublime hymn of glorification of external Nature. The way these different senses lie in some passages one behind the other, and are in others inextricably blended together, defies comment. But beyond all, the chief difficulty in criticising this, as all other poems in Leaves of Grass, is that the ideas expressed are of scarcely any value or importance compared with the passion, the never-flagging emotion, which is in every line, almost in every word, and which cannot be set forth or even touched by commentary. If, again, the reviewer tries to impress the deeper meaning upon his reader by quoting passages, he finds that this expedient is equally futile, because no extract will make upon the reader an impression at all corresponding to that produced by the same lines upon a person to whom the whole poem is familiar. The " Song of Myself" is not only a celebration of man (any man), his soul and body, but it is a celebration of everything else as well (necessarily so, since, as Walt Whitman expresses it, "Objects gross and the unseen soul are one ")—of the earth and all there is upon it—of the universe, and of the Divine Spirit that animates it—that is it. The reader is not merely told that these things are good, and persuaded or

argued into believing it (that has been done a thousand times, and is a small matter), but he is brought into contact with, and absolutely fused in the living mind of Walt Whitman, to whom these things are so, not as a matter of speculation and belief, but as a matter of vital existence and identity: and as he reads the poem (it may be for the fifth or the fiftieth time), the state of mind of the author inevitably (in some measure) passes over to the reader, and he practically becomes the author—becomes the person who thinks so, knows so, feels so. But, until this point is reached (and with many readers, so far, it is never reached), the poem is necessarily more or less meaningless, and besides is displeasing from what critics call its "egotism," a quality well known to the author, who (in the first as well as subsequent editions) says:

I know perfectly well my own egotism.

Know my omnivorous lines, and must not write any less,

And would fetch you whoever you are flush with myself.

When the reader is brought " flush " with or up to the spiritual level of the book (if this ever happens), he finds, as Walt Whitman tells him, that it is himself talking just as much as the man who wrote the book—that in fact the "ego" is the reader fully as much as the writer. The poet speaks for himself in the first place of course, but he speaks also just as much for others, as he says :

It is you talking just as much as myself, I act as the tongue of you, Tied in your mouth, in mine it begins to be loosen'd.

Then the range is outdoors almost perpetually. No critic of the poems can fail to notice the entire absence of any bookshelf or easy-chair character in them. Many readers will consider it a fault; at any rate the pieces, from first to last, give out nothing of the atmosphere of a permanent indoor home.*

* " Poets' Homes " for 1879 (Mrs. Mary Wager-Fisher) says : As to Walt Whitman's home, it must be confessed that he has none, and for many years has had none in the special sense of "home;" neither has he the usuallibrary or " den" for composition and work. He composes everywhere—years ago, while writing Leaves 0/ Grai-.r, sometimes on the New York and Brooklyn ferries, sometimes on the top of omnibuses in the roar of Broadway, or

One peculiarity is the indirectness of the language in which it is written. This is at first a serious obstacle to the comprehension of the poems, but after the key has been found, it adds materially to the force and vividness of expression. In places where a thought or fact is expressed in the usual direct manner, there is frequently a second and even a third meaning underlying the first. The following examples, which are taken from the " Song of Myself," will serve to give an idea of the feature in question, which belongs more or less to the whole volume:

Houses and rooms are full of perfumes, the shelves are crowded with perfumes, I breathe the fragrance myself and know it and like it, The distillation would intoxicate me also, but I shall not let it.

The atmosphere is not a perfume, it has no taste of the distillation, it is odorless, It is for my mouth forever, I am in love with it,

I will go to the bank by the wood and become undisguised and naked, I am mad for it to be in contact with me.

In this passage "Houses and rooms" are the schools, religions, philosophies, literature ; " perfumes " are their modes of thought and feeling; the "atmosphere" is the thought and feeling excited in a healthy and free individual by direct contact with Nature; to be "naked" is to strip off the swathing, suffocating folds and mental wrappings derived from civilization.

Stop this day and night with me, and you shall possess the origin of all poems,

means, Live with me (with .my book) until my mode of thought and feeling becomes your mode of thought and feeling.

I have heard what the talkers were talking, the talk of the beginning and the end,

amid the most crowded haunts of the city, or the shipping by day—and then at night, often in the democratic amphitheatre of the Fourteenth Street Opera House. The pieces in his "Drum Taps " were all prepared in camp, in the midst of war scenes, on picket or the march, in the army. He now spends the summers mostly at a solitary farm " down in Jersey," where he likes best to be by a secluded, picturesque pond on Timber Creek. It is in such places, and in the country at large, in the West, on the Prairies, by the Pacific—in cities too, New York, Washington, New Orleans, along Long Island shore where he well loves to linger, that Walt Whitman has really had his place of composition.

14

means, I have studied what has been taught in the philosophies and religious systems as to the Creation or the final destinies and purposes of men and things.

I am satisfied—I see, dance, laugh, sing;

As the hugging and loving bed-fellow sleeps at my side through the night, and

withdraws at the peep of the day with stealthy tread. Leaving me baskets cover'd with white towels swelling the house with their

plenty, Shall I postpone my acceptation and realization and scream at my eyes That they turn from gazing after and down the road. And forthwith cipher and show me to a cent. Exactly the value of one and exactly the value of two, and which is ahead ?

means, I am contented and happy as I am; refreshed with sleep, I have all I need ; that being the case, shall I put off the enjoyment of life, and blame myself that I do not take part with the world in studies, money-making, ambition and the like, or spend my time calculating what is best to do, say, etc. ?

Long enough have you dream'd contemptible dreams; Now I wash the gum from your eyes.

You must habit yourself to the dazzle of the light and of every moment of your life;

Long have you timidly waded holding a plank by the shore; Now I will you to be a bold swimmer.

To jump off in the riiidst of the sea, rise again, nod to me, shout, and laughingly dash with your hair;

means, You have long enough been degraded by ancient superstitions, followed the systems, the schools, the religions handed down from old times, all taken for granted, wanting courage to look for yourselves; now I propose to have you face all things and your fortunes with confidence and faith, and live a free and joyful life.

I swear I will never again mention love or death inside a house,

means, I will never more think, or have you think, of love or death in the conventional ways, with the old limitations (the walls of the house) or with the feeling of dread (in the case of death).

And filter and fibre your blood,

means, and purify and strengthen your spiritual nature.

These examples might be multiplied to almost any extent, for a large part of this poem, as of all Leaves of Grass, is made up of language which I have characterized as indirect, but which, when understood, is seen to be more direct than any other. This "Song of Myself" is, in the highest sense of the word, a religious poem. From beginning to end it is an expression of Faith, the most lofty and absolute that man has so far attained. There are passages in it expressive of love or sympathy, but taken as a whole, the groundwork and vivifying spirit of the poem is Faith.

Following the "Song of Myself," comes the group called "Children of Adam." ("He that will deepest serve men," says De Foe, " must not promise himself that he shall not anger them.") These poems having been misunderstood, as was indeed inevitable at first, have given rise to condemnatory criticism not only against the pieces themselves (which really form a small proportion of the whole work), but against the rest of the book, and its author. Perhaps these poems can only be justified as they justify themselves, by altering the mental attitude of society and literature towards the whole subject treated in them ; and this of course will take time, no doubt several generations. For, though to a few thoughtful people, women as well as men, these parts either require no justification, or are already justified by the process indicated, yet probably the vast majority of persons now living in the most civilized countries could never be got to believe, and could never if they tried make themselves see, that the mental attitude represented by Walt Whitman is higher and better (as it certainly is, and time will prove itj than has before existed towards all things relating to sex. The following on the subject is from a criticism by Joseph B. Marvin in the Boston quarterly " Radical " for August, 1877 :

There are two phases of Whitman's poetry we have barely alluded to: his treatment of sex, and his form of expression; his celebration of amativeness, and his art. It is these, chiefly, that have given offence. As to the first—as to sexuality—there is an instinct of silence, which, it is said, Whitman, in his

group of poems entitled " Children of Adam " rudely ignores and overrides. But so does the physiologist and the true physician ignore this instinct and break the silence : and properly so. And this poet of Democracy is a physician of both soul and body. He comes to diagnosticate the disease in the intellect, in the art, in the heart, of America to-day. And what does his discriminating eye discern ? He sees that there is a false sense of shame attaching, in the modern mind, to the sexual relation. There is tacit admission among men and women everywhere, in our time, that there is inherent vileness in this relation, in sex itself, and in the body. We come honestly enough by this belief. The tradition is very old. It began witli Judaism, and Christianity has maintained it. The Church chants it in her litanies; and Puritanism has emphasized it, and formulated it into an iron creed. The body's vileness is traced back in our traditions even to the beginning of the human race. Nor is there any concession of the possibility of purification on the earth. Was it not time that one came who should break the long silence about sexuality ? who should show that what men have been dumb about, and ashamed of, through all these years, is not foul, but holy—holy as love; holy as birth, and fatherhood, and motherhood, to which it all pertains? And who, better than the poet, was entitled and qualified to perform this service ? For, to him, the real is visible always in its ideal relations. And did not the achievement of this high task and service devolve naturally and especially upon the poet of Democracy; upon him who is distinctively the attestor and celebrator of the greatness and the divineness in men and women; who is the interpreting, rapt Lucretius of human nature ? Before Whitman came, there had been plenty of half-praise of human nature, and no end of the demagogue's vulgar flattery. But at last comes one who reveres mankind; by whom all, all of man is honored; and in whose eyes sexuality, the body, the soul, are equally pure and sacred. Again, was it not fitting that he who has celebrated death as has no other poet, should likewise celebrate birth: and not only birth, but the prelude of birth,—procreation and begetting ?

And now at length, the task achieved, this service to humanity performed, let the instinct of silence, if you will, again prevail. The purpose for which the spell was broken is accomplished. The flesh is freed from its false repute. The " fall" is finished. Henceforth humanity ascends. Democracy now for the first time interpreted and understood, man may begin to achieve his destiny intelligently, and in fulness of self-respect.